The story of Budapest is as layered and dynamic as the city itself—a tale that begins in prehistory and winds its way through conquest, cultural rebirth, and modern reinvention. Buda – west side of the Danube -is the upper-class, ritzy area complete with a castle. It’s filled with lots of museums, historic streets, beautiful parks, and regal homes. Pest, on the other hand, is on the eastern side of Danube.

History of Budapest

Long before, this area was home to Celtic tribes. Around the 1st century BC, the Celts settled along the Danube River. In AD 89, the Romans conquered the region and founded the town of Aquincum in what is now Obuda (Old Buda). Aquincum served as the capital of the Roman province of Pannonia and was a major military stronghold. Remnants of Roman baths and amphitheaters can still be seen today.

By the end of the 9th century, Magyar tribes arrived from the East. In 896 AD, under the leadership of Árpád, they established what would become the Kingdom of Hungary. The hillier western side of the Danube—today’s Buda—grew into a seat of royal power, while Pest across the river evolved as a busy commercial hub. Mongols invaded the kingdom of Hungary in 13th century and brought upon devastation of massive scale. King Béla IV rebuilt the country’s fortresses in stone, including the stronghold at Buda, giving birth to the medieval cityscape. 15th century was the golden period for Hungary under king Matthias Corvinus, who invited artists and scholars from across Europe. Buda became a Renaissance capital. However, in the battle of Mohacs in 1526, Ottomans gained sovereignty over Transylvania (Romania) or Eastern Hungarian Empire and Austrians got western part of kingdom of Hungary, kingdom of Bohemia and Croatia. After almost 150 years of Turkish rule, Habsburgs recaptured Buda in 1686. Over time, the city was rebuilt in the Baroque style. The 19th century brought rapid industrialization and a nationalist movement. In 1873, Buda, Pest, and Obuda were officially united to form Budapest. The city blossomed during the Austro-Hungarian Empire, gaining architectural treasures like the Parliament Building and Heroes’ Square.

World War II devastated Budapest, with the Siege of Budapest in 1945 reducing much of it to rubble. The Soviet Union’s grip tightened after the war, culminating in the failed 1956 Hungarian Revolution. Many historical buildings were destroyed or left neglected during Communist rule. Following the fall of the Iron Curtain in 1989, Budapest emerged as a vibrant European capital, embracing democracy and free-market reforms. Today, it is a city where Roman ruins, Ottoman baths, Baroque palaces, and modern design coexist—a living museum with a forward-looking soul.

Public transportation in Budapest

Budapest boasts one of the most efficient and affordable public transportation systems in Europe. The network includes metro, trams, buses, boats and funiculars. To navigate all of this download, BudapestGO app by BKK. We took 72-hours pass. You can plan multi-modal journeys, buy and validate tickets through this app.

Important tip – You must validate with your app every time you take a trip, even though you have the pass. Validation can be done by scanning a QR code at the mode of transport and showing the resulting animation in the app to the ticket inspector when asked. It is a rule and very strictly enforced.

Day 1, Dec 27th 2024

We arrived in Budapest on a Regio Jet train from Vienna by 1:30 PM. The journey was comfortable and scenic, offering a glimpse of Hungary’s changing countryside. We took the metro from the railway station to Batthyány tér metro station. Our Airbnb was walking distance from here. We freshened up and immediately headed out.

Free walking tour

At 3:30 PM, we joined a free walking tour booked through freetour.com by Generation Tours Budapest. The tour began at Madách Imre tér, next to a striking statue of Empress Sisi—a historical reminder of Hungary’s imperial past. Our guide was fantastic – funny, informed, and full of energy. These walking tours are a great way to anchor yourself in a new city and get a visual introduction to the key landmarks and neighborhoods. We did the same thing in Prague, Vienna and Bratislava in this trip.

We saw some wonderful things during our tour. We started with Gerbeaud Café and Vörösmarty tér. One of Budapest’s most famous cafés, Gerbeaud sits on the edge of Vörösmarty tér—a bustling public square often filled with events. The café, founded in 1858, is known for its opulent interiors and rich pastries. It also has oldest underground tunnel built beneath it. A surprising landmark we saw in the European capital was Michael Jackson tree. It is a fan-made tribute outside the Kempinski Hotel where the King of Pop once stayed. Fans plastered the tree with photos, candles, and handwritten notes. Tucked discreetly beneath the city, our guide pointed out a cold war-era nuclear bunker. These are remnants of a time when the city lived under the constant threat of Soviet-era paranoia. At Szabadság tér (Liberty Square), we saw the Soviet War Memorial, which honors soldiers who died liberating Budapest from Nazi forces. It stands amidst controversy and history, juxtaposed with statues critical of Soviet occupation. Just a few meters away stands a bronze statue of Ronald Reagan, walking toward the U.S. Embassy. Installed in 2011, it symbolizes Hungary’s appreciation for Reagan’s role in ending the Cold War and Soviet influence.

In 2014, Monument of German Occupation was erected in Liberty Square. It had archangel Gabriel holding a golden orb and being attacked by a menacing eagle. Archangel Gabriel represented Hungary with the orb representing its sovereignty and the eagle represented Nazi Germany. This sparked major controversy as it completely whitewashed Hungary’s role in the Holocaust. Hungary was not an innocent victim of Nazi Germany but rather an active collaborator. More than 400,000 Jews were mass deported in less than 2 months. Therefore, it was criticized as an attempt to shift historical blame solely to Nazi Germany, ignoring Hungary’s complicity. In response to the monument, a counter-memorial was created right in front of it. Personal items like shoes, newspaper articles and photographs of holocaust victims or survivors were kept in front of it with stones.

Although we didn’t cross over, the sight of Buda Castle from the Pest promenade was stunning. Perched atop Castle Hill, this grand structure dominates the skyline and embodies centuries of Hungarian royalty and resilience. The Chain Bridge, completed in 1849, was the first permanent bridge connecting Buda and Pest. At sunset, its lion statues and glowing lamps cast a magical aura over the Danube. We concluded with views of the grand Hungarian Parliament, one of Europe’s largest and most ornate legislative buildings. Its neo-gothic architecture and riverside location make it one of Budapest’s most photogenic spots.

The walking tour ended around 5:30 PM, leaving us with a strong foundational understanding of the city.

Christmas market outside St. Stephen’s Basilica

In the evening, we explored the Christmas market outside St. Stephen’s Basilica—easily one of the best we’ve seen in this trip to central Europe. The market was lively, well-organized, and filled with food stalls, craft vendors, and warm lights. The real highlight? The hourly light show projected on the front façade of the Basilica. It was a magical blend of sound and visuals that stopped everyone in their tracks.

Day 2, Dec 28th 2024

Our second day in Budapest was packed with history, architecture, and soul-stirring sights. We focused on the Buda side of the city—its hills home to some of Hungary’s most iconic landmarks.

Fisherman’s Bastion

Perched like a fairytale fortress on Castle Hill, Fisherman’s Bastion offers panoramic views of the Pest side and the Danube below. Despite its fortress-like name and appearance, Fisherman’s Bastion was never a true defensive fortification. It was constructed between 1895 and 1902 as part of a broader campaign to beautify and commemorate Hungary’s millennium in 1896, which marked 1000 years since the arrival of the Magyar tribes in the Carpathian Basin. The name honors the guild of fishermen who defended this section of the city walls in the Middle Ages. The Bastion was designed by Frigyes Schulek, a prominent Hungarian architect who was also responsible for the restoration of the adjacent Matthias Church.

With its seven conical white turrets representing the seven Magyar tribes who settled the Carpathian Basin in 896 AD, the structure feels more like a Disney set than a military fortification. It is easy to confuse turrets with towers. Towers go all the way to the ground and have their own foundation. Turrets emerge from the building part way up, hanging over empty space below. Built using white limestone, Firsherman’s Bastion exudes a golden glow at sunrise and sunset. Its arched colonnades, winding staircases, and lookout terraces makes it a photographer’s dream.

The structure was damaged during World War II, like much of Budapest, and was restored by Frigyes Schulek’s son, János Schulek, who carefully rebuilt it in line with the original plans.

The Church of Our Lady (Matthias Church)

Just beside Fisherman’s Bastion stands the dazzling Church of Our Lady, better known as Matthias Church. This gothic masterpiece dates back to the 13th century and has been a witness to coronations, battles, and reconstructions. It was built by King Bela IV around 1255 after devastating Mongol invasion. It’s where Franz Joseph I and Empress Elisabeth (Sisi) were crowned as rulers of Hungary in 1867. During Ottoman’s rule of Buda, this church was converted into a mosque and many of its Christian elements were either covered or plastered over.

By the 18th century, the church had fallen into disrepair. The most transformative renovation came in the late 19th century, led by renowned Hungarian architect Frigyes Schulek. Schulek not only restored the crumbling gothic structure but also added neo-gothic elements, redesigned the roof with colorful Zsolnay tiles, and introduced detailed frescoes and ornate carvings in the interior. The renovations were completed by 1896, coinciding with Hungary’s Millennium celebrations marking 1000 years since the Magyars’ arrival.

From the outside, the church’s most eye-catching feature is its colorful tiled roof made from Zsolnay ceramics that shimmer in green, orange, and gold. But the true marvel is the interior where every pillar, wall, and arch are intricately painted in warm maroon, blue, and gold hues. It feels like walking into a jewel box of sacred art. We marveled at the exquisitely carved and painted pulpit, a gothic gem with floral designs and tiny statues showcasing the scenes of New Testament. The Holy Trinity Chapel glowed in golden tones, housing a replica of the Holy Crown of Hungary. Nearby, is the tomb of King Béla III and his wife, one of the oldest royal tombs in Hungary.

There is a museum within the church that houses religious relics and historical artifacts on upper floors. The upper floor gives an astonishing view of the nave and altar allowing us to appreciate the church’s full spatial grandeur.

At the back of the nave of the church is an elevated section. There is a sacred artistic motif depicting Lamb of God looking down over the nave and the main altar. In Christianity, the Lamb of God symbolizes Jesus Christ’s sacrificial role and his divine nature.

Outside the church stands the Holy Trinity Statue, erected in 1713 as a thanksgiving offering after the end of a devastating plague. It’s richly decorated with angels, saints, and baroque flourishes.

The church is popularly known as Matthias Church because King Matthias Corvinus, one of Hungary’s most beloved monarchs (reigned 1458–1490), restored and expanded it in the late 15th century. His emblem—the raven with a ring—can still be found in parts of the church’s decoration.

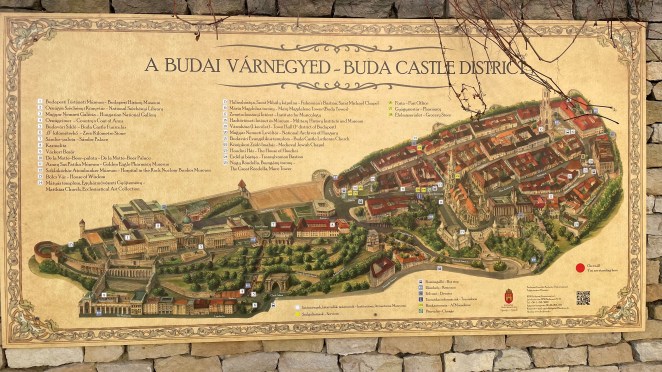

Buda Castle District

We walked through the charming Buda Castle District, with cobblestone streets and baroque townhouses exuding an old-world charm. On the way, we stopped for a chimney cake—a warm, spiral-shaped pastry dusted with cinnamon sugar. A local delight, perfect fuel for castle exploration.

Buda Castle

Once the royal residence of Hungarian kings, Buda Castle (Budavári Palota) is now a cultural hub, home to museums and galleries. The castle complex has gone through centuries of rebuilding and destruction, most notably during World War II, when heavy bombing razed much of it to ruins.

Today, the site is undergoing a massive restoration effort under the National Hauszmann Program, which aims to reconstruct many lost or damaged sections in their original historic style. While this is admirable, we found it slightly underwhelming to realize that much of what we see today is reconstructed, not original.

Still, several elements stood out. At the entrance of the castle is a dramatic eagle statue, symbol of the Turul (a mythic Hungarian bird), perched high on a plinth and watching the Danube. The equine statue of Prince Eugene of Savoy at the front is a nod to his victory over the Ottomans. The imposing Matthias Fountain is a sculptural tableau showing King Matthias Corvinus hunting with his hounds. The woman watching is said to be Ilonka, his love, who died of heartbreak. The inner courtyard of the castle is flanked by grand staircases and guarded by two lion statues at the entrance.

We also saw the funicular bringing people up and down the castle hill—a scenic but crowded ride. Judging by the long queues, we were glad we chose to walk.

Chain Bridge

The story goes that Count István Széchenyi missed his father’s funeral in Vienna because the ferry across the Danube couldn’t operate due to it being frozen. Frustrated by the inconvenience and the lack of a permanent crossing between Buda and Pest, he vowed to support the construction of a bridge. The bridge was designed by William Tierney Clark, a British engineer, and built under the supervision of Adam Clark (no relation), a Scottish engineer.

Crossing the Chain Bridge, Budapest’s first permanent bridge over the Danube, was like stepping back into the 19th century. Completed in 1849, it was a marvel of engineering at the time. The lion statues at each end are iconic, and the bridge offers unbeatable views of both Buda Castle and Parliament—especially magical at twilight. In 1945, retreating German troops blew this bridge. It was reconstructed in 1949, as it is today.

Great Market Hall

From history to culinary culture, we headed to the Central Market Hall, Budapest’s largest and most vibrant indoor market. Built in 1897, it features three floors of food, souvenirs, and crafts. The ground floor is a paradise of paprika, sausages, cured meats, and fresh produce. Locals were buying thick slabs of bacon and smoky sausages with practiced ease. Upstairs, the balcony level houses souvenir shops and food stalls selling langos, goulash, and chimney cake. It’s busy, but worth navigating for a taste of traditional Hungarian cuisine in a lively atmosphere.

St. Stephen’s Basilica

Returning to the Pest side, we visited the majestic St. Stephen’s Basilica, named after Hungary’s first king, St. Stephen I (Istavan in Hungarian), who converted the nation to Christianity. Finished in 1905, the basilica is an architectural blend of neo-classical grandeur and renaissance detail. It stands 96 meters tall and as a mark of respect, no building in Budapest is taller than 96 meters.

To enter the basilica, you must purchase a ticket, which we did. And it was well worth it. The soft lighting illuminated the interior’s intricacies—from saints in alcoves to cherubs above the altar. The interior is magnificent, with golden domes, rich marble columns, and delicately painted frescoes. Each arch and altar is a testament to the country’s religious devotion and artistic legacy.

One of the most unusual attractions is the Holy Right Hand—a mummified relic of King Stephen’s hand, preserved in a golden reliquary in the chapel.

As night fell, the Christmas market outside the Basilica lit up the square. The festive lights, artisan stalls, and smell of mulled wine created a magical winter vibe. Choir music and twinkling garlands added charm to every corner. With the Basilica’s grand dome glowing above, we sipped hot drinks and browsed handcrafted ornaments and Hungarian street food. It was the perfect way to end a full day—rooted in history, elevated by architecture, and wrapped in the warmth of the season.

Day 3, Dec 29th 2024

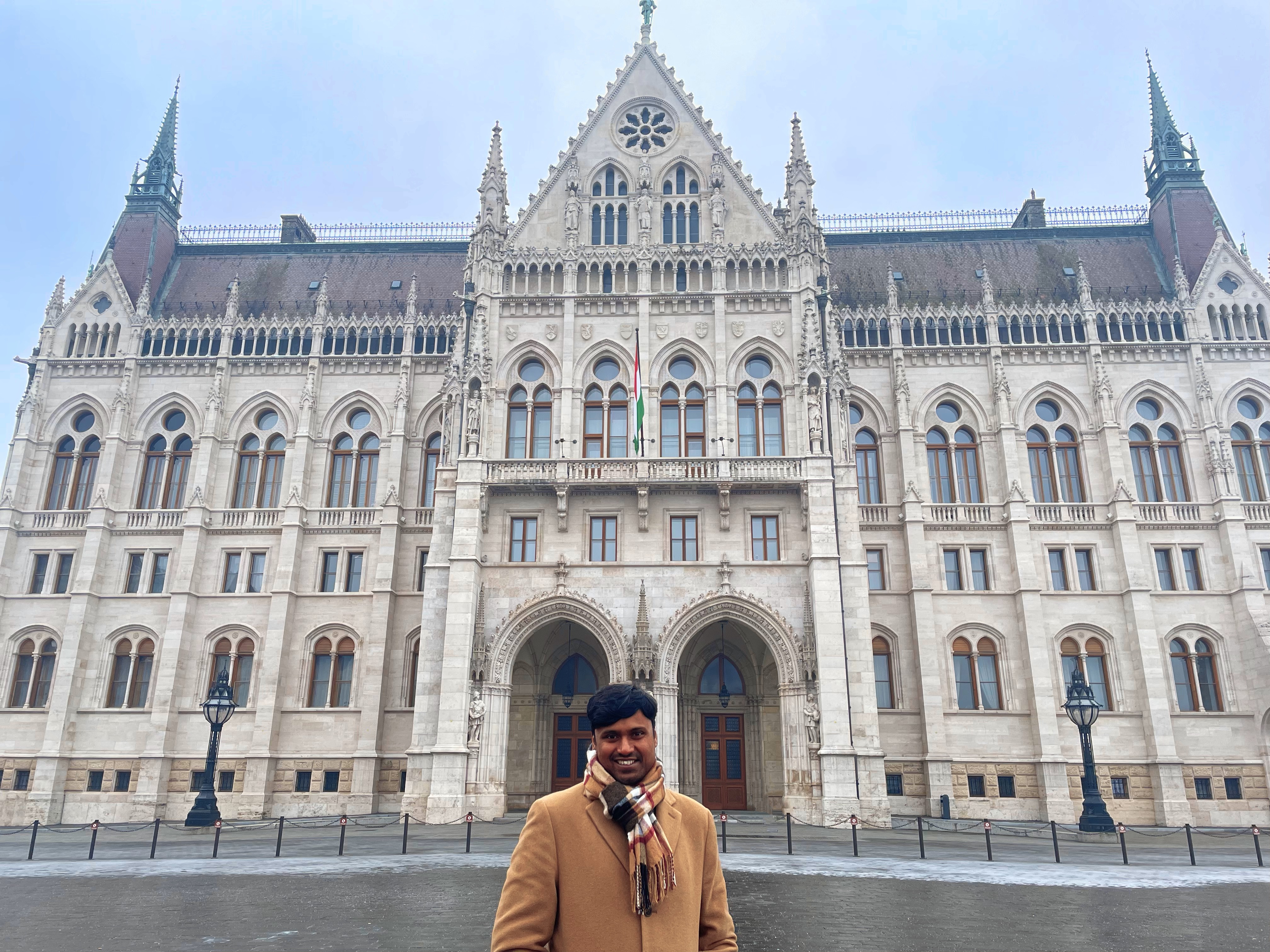

Hungarian Parliament

We began the day at the Hungarian Parliament, one of the most iconic and recognizable landmarks in Budapest. Perched along the banks of the Danube, the building was shrouded in a soft winter mist that morning — giving it a mystical, ethereal look. The architecture of this building was inspired by Vienna City Hall. Opened in 1902, this building is the largest building in Hungary ever since. It houses over 691 rooms, 10 courtyards, 29 staircases, and 242 sculptures inside.

Unfortunately, we couldn’t take the guided tour — tickets were already sold out for the day. I had assumed we could book it on arrival, but I misjudged.

Important tip: Book your Parliament tour well in advance — ideally the moment your Budapest plans are finalized.

Shoes on the Danube bank

Our next stop was nearby Shoes on the Danube Bank, one of the most moving memorials I’ve ever seen. Bronze shoes — of men, women, and children — are lined up at the water’s edge, as if the people wearing them had just vanished. Erected in April 2005 on Danube Promenade, this memorial honors the thousands of Jews who were murdered along the Danube during World War II by the Arrow Cross Party, a fascist group aligned with Nazi Germany. Victims were ordered to remove their shoes (shoes were valuable and could be used for military) before being shot so their bodies would fall into the river and be swept away.

House of terror museum

By late morning, we made our way to the House of Terror Museum, a grim yet essential visit for anyone wanting to understand Hungary’s 20th-century history. The museum is housed in the former headquarters of the ÁVH (State Protection Authority) — Hungary’s Communist-era secret police. Before that, during World War II, it was used by the fascist Arrow Cross Party. The building became a site of interrogation, torture, and death. The museum chronicles the twin totalitarian regimes (Nazi and Communist) that Hungary endured from 1944 to 1989.

Multimedia exhibits, prison cells, personal testimonies, and a chilling basement detention center all come together to tell the stories of those who were silenced. It sent shivers down my spine. It’s not an easy visit but it’s an important one. It’s a tribute to the resilience of those who suffered and a reminder of the cost of tyranny.

As I came out of House of Terror, is evoked a strong feeling that that India, too, needs a dedicated museum to chronicle the immense suffering endured under British colonial rule. Such a museum could serve as a poignant reminder of events like the Jallianwala Bagh massacre of 1919, where British troops opened fire on peaceful protestors, killing hundreds without warning. It would highlight the Bengal Famine of 1943, in which an estimated 3 million people perished—largely due to deliberate wartime policies and neglect by the colonial administration. Brutal repression of the 1857 revolt, the exploitation of Indian soldiers in World Wars, merciless torture of Indian freedom fighters, divide & conquer policies of British leading up to the painful partition in 1947 and not to forget the systematic economic drain that impoverished the nation during its 200 years of rule. India ought to have a museum that chronicles all of these.

Ruin bar – Szimpla Kert

In search of a mental break, we headed to Szimpla Kert, the most famous of Budapest’s ruin bars. These quirky, eclectic bars are a defining part of the city’s nightlife. Ruin bars emerged in the early 2000s, transforming abandoned buildings in Budapest’s Jewish Quarter into lively social spaces. Szimpla Kert opened in 2002 in a dilapidated factory and sparked a cultural movement. With mismatched furniture, surreal art, and a bohemian vibe, it has become a symbol of creativity rising from decay.

We had fajitas, nachos, and beer — not extraordinary food, and a bit on the pricey side — but the atmosphere made up for it.

Heroes’ square

After lunch at Szimpla Kert, we made our way to Heroes’ Square, one of the most significant and impressive public spaces in the city. Its construction began in 1896 for Hungary’s Millennium Celebrations. The square commemorates the thousandth anniversary of the arrival of the Magyars in the Carpathian Basin.

Th square features Millennium Monument at the center with statues featuring the Seven chieftains of the Magyars and other important Hungarian national leaders, as well as the Memorial Stone of Heroes. The semi-circular colonnades behind the column feature statues of Hungary’s most revered kings, leaders, and statesmen — from Saint Stephen, the founder of the Christian Hungarian state, to Matthias Conrvinus. The square is flanked by two major museums: the Museum of Fine Arts and Műcsarnok (Hall of Art).

We ended the day with ice cream at Gelarto Rosa and a chimney cake.

As the final stop on my Central Europe adventure, Budapest felt like the perfect farewell — a city that captures the heart with its rich history, grand architecture, and soulful charm. From the shimmering Danube to the glowing spires of St. Stephen’s Basilica, every moment here felt like a celebration of culture and resilience. Walking through its festive Christmas markets and timeless landmarks, I found not just the end of a journey, but a city I’ll carry with me long after the trip is over.