The idea of this trip wasn’t years in the making—it arrived out of the blue one quiet afternoon in May 2025. We were driving back from our Poulsbo trip when we passed an RV rental lot. Both Raj and I admitted, almost at the same time, that we had always wanted to try driving an RV. Doing it alone felt intimidating but doing it together suddenly felt exciting and safe. And just like that, the spark became a plan. The destination we landed on was none other than Alaska. Alaska had always lived in my imagination as a far-off land of mountains, glaciers, and midnight sun—beautiful, yes, but distant and almost unreal. By the next weekend, our tickets and RV were booked.

What followed over 12 days was a story of discovery – not just of mountains, but also us. These upcoming blog posts capture each day of that journey, from the awe of first sightings to the quiet moments by rivers, from the thrill of flightseeing to the simplicity of home-cooked meals, and from the vast landscapes to the small joys of travel. This is our Alaska—not just a destination, but an experience that began on a whim and became a memory we will carry forever.

Itinerary at a glance

| Day | Date | Itinerary | Campgrounds |

| Day 1 | June 23rd, 2025 | Fly from Seattle to Anchorage, Drive to Homer | Ocean Shores RV Park |

| Day 2 | June 24th, 2025 | Homer to Seward | Stoney Creek RV Park |

| Day 3 | June 25th, 2025 | Wildlife boat tour, Seward | Stoney Creek RV Park |

| Day 4 | June 26th, 2025 | Seward to Talkeetna | Boondock at Talkeetna Air Taxi |

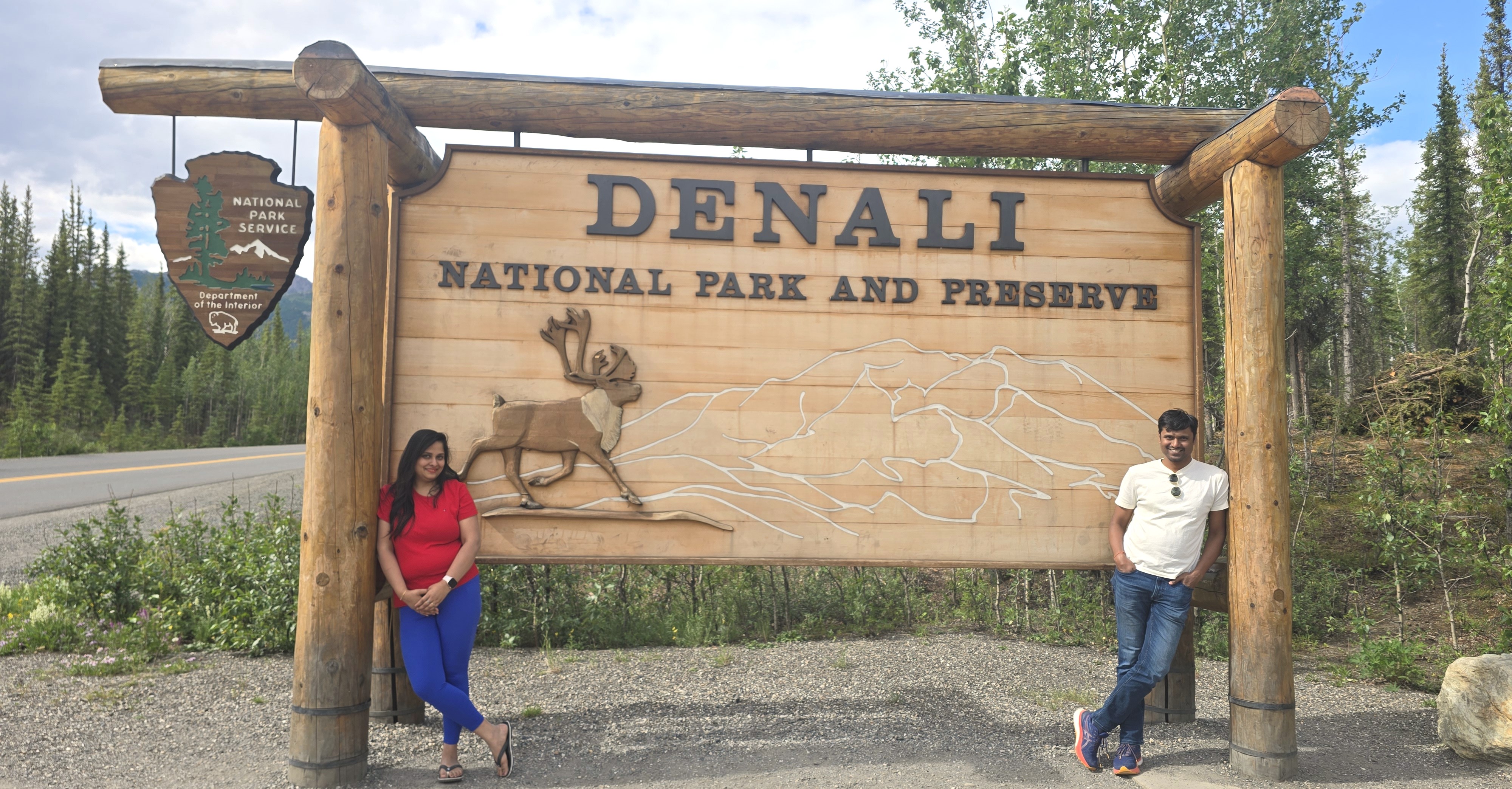

| Day 5 | June 27th, 2025 | Talkeetna to Denali | Riley Creek campground |

| Day 6 | June 28th, 2025 | Denali to Glennallen | Ranch House Lodge |

| Day 7 | June 29th, 2025 | Glennallen to Chitina | Boondock at Pippin Lake |

| Day 8 | June 30th, 2025 | Chitina to Valdez | Bear Paw RV Park |

| Day 9 | July 1st, 2025 | Valdez to Matanuska | Boondock near Matanuska |

| Day 10 | July 2nd, 2025 | Matanushka to Hatcher’s pass | Boondock at Fishhook trailhead near Hatcher’s Pass |

| Day 11 | July 3rd, 2025 | Hatcher’s pass to Anchorage to Whittier | Boondock at Portage Lake |

| Day 12 | July 4th, 2025 | Whittier to Anchorage, fly back to Seattle | — |

Seward’s folly or jackpot?

Long before it appeared on U.S. maps, Alaska was home to diverse indigenous cultures whose traditions and trade networks thrived for thousands of years. European interest arrived in the 18th century with Russian fur traders, who established outposts and dominated the lucrative sea otter trade. By the mid-19th century, Russia, burdened by war debts and fearing British expansion, decided to sell its distant colony. In 1867, U.S. Secretary of State William H. Seward negotiated the purchase for $7.2 million—about two cents an acre. Critics ridiculed the deal as “Seward’s Folly” and “Seward’s Icebox”. Many were convinced that U.S. had bought a frozen wasteland. History proved them spectacularly wrong: the land would later yield gold, oil, and strategic value beyond imagination.

The Klondike and Nome gold rushes of the late 1890s transformed Alaska almost overnight. Prospectors poured in, boomtowns sprang up, and the territory’s population surged, setting the stage for greater U.S. investment. Alaska became an official U.S. territory in 1912, but it wasn’t until January 3, 1959, that it achieved statehood as the 49th state—after decades of debate over its remoteness and economic viability. Ironically, the very isolation that once made Alaska seem like a liability became part of its allure.

Today, Alaska is a land of superlatives. At 586,000 square miles, it’s larger than Texas, California, and Montana combined. It boasts more coastline than the rest of the United States put together and contains some of the wildest landscapes on Earth. Its national parks are on a scale that defies comparison: Wrangell–St. Elias alone spans 13.2 million acres—bigger than Switzerland—and Denali National Park shelters North America’s tallest peak at 20,310 feet. From volcanic arcs to vast glaciers, Alaska’s story is one of extremes, resilience, and a constant reminder that nature, here, still calls the shots.

Geography of Alaska

Alaska’s geography reads like a catalog of extremes, stretching from the temperate rainforests of the southeast to the treeless Arctic tundra at the top of the world. The state’s famous Inside Passage threads through the glacier-carved fjords and island labyrinth of the Alexander Archipelago, where steep, forested slopes plunge into deep, green channels. Moving west and north, the land bulks up into great mountain systems—the snow-loaded Chugach and Wrangell–St. Elias ranges along the Gulf of Alaska and the Alaska Range arcing across the interior, home to Denali, North America’s tallest summit. Farther still, the Brooks Range forms a rugged continental divide before the ground flattens into the coastal plain of the Arctic, a treeless expanse under a vast sky that glows with midnight sun in summer and starlit auroras in winter.

Water defines Alaska as much as rock and ice. The state’s coastline is longer than that of all the other U.S. states combined, scalloped by the Gulf of Alaska and the Bering, Chukchi, and Beaufort seas. The Aleutian Islands—an immense volcanic chain—sweep like a stone necklace into the North Pacific, marking the restless edge of the Ring of Fire. Inland, broad rivers such as the Yukon and Kuskokwim wander for hundreds of miles across spruce forest and muskeg, while the Copper and Susitna slice out of glacier country toward the sea. Tens of thousands of glaciers drape Alaska’s high country and fjords, from the sprawling Juneau Icefield to tidewater giants like Hubbard and Columbia, calving blue bergs into icy bays.

Scale is the through line. Alaska is larger than Texas, California, and Montana combined, yet its population is sparse, and the land remains largely wild. That immensity holds a mosaic of ecosystems: the towering old-growth of the Tongass National Forest in the southeast; a vast interior of boreal forest and permafrost; and, in the north, low, hardy tundra adapted to permafrost and fierce winds. The weather swings with latitude and ocean influence—maritime and wet in the southeast, continental and sharply seasonal in the interior, and austere in the Arctic—while daylight itself becomes a geographic feature, with months of long, luminous days followed by seasons of lingering twilight. Taken together, these forces—mountain, ice, ocean, and light—shape a place where geography isn’t backdrop but main character.

National park vs national park units

National Parks are the top-tier protected areas in the United States. They are designated specifically for their outstanding natural beauty, unique geological features, and ecological importance. There are 63 official National Parks in the U.S., 8 of which are in Alaska – Denali National Park & Preserve, Gates of the Arctic National Park & Preserve, Glacier Bay National Park & Preserve, Katmai National Park & Preserve, Kenai Fjords National Park, Kobuk Valley National Park, Lake Clark National Park & Preserve, Wrangell–St. Elias National Park & Preserve.

National Park Units, on the other hand, include everything the National Park Service manages — not just parks. This includes national monuments, preserves, seashores, historic sites, recreation areas, battlefields, parkways, and more. Altogether, there are over 400 National Park Service units in the U.S, 24 of which are in Alaska.