Day 6, June 28th

Day 6 had a slow and relaxed start. We took warm showers at the Riley Creek campground’s mercantile. Near the mercantile there is fresh water and sewer dump stations. Our RV was ready for today’s adventure.

First we went to Denali Park Village. It is a complex with hotels, shopping complex, theatre and restaurants. But it was surprisingly empty, devoid of any people. We went to the souvenir shop and purchased few magnets.

Denali Highway – the forgotten backroad to Alaska’s heart

Our original plan was to head north toward Fairbanks, but a wildfire had closed part of the highway. The alternate route would have doubled travel time, so we decided instead to take the Denali Highway, a 135-mile ribbon of wilderness running east–west, connecting AK-Route 3 with AK-Route 4.

Once the only road to Denali National Park (before the Parks Highway opened in the 1970s), the Denali Highway was historically the access route used by early mountaineers, rangers, and Native families traveling between summer and winter hunting grounds. Today, the highway feels like untouched Alaska—remote, raw, and absolutely breathtaking.

But beauty came with bumps. The Denali Highway is only partly paved and notoriously rough, a result of both minimal road maintenance and the permafrost beneath. Frozen ground expands in winter and thaws unevenly in summer, creating dips, cracks, and potholes that shift every year. RV companies allow driving here but advise frequent tire checks. Only after a few miles we understood exactly why.

Still, the views were the best of the trip so far. Endless mountains, rolling tundra, shimmering lakes, and clouds that seemed to sit right on the ridgelines. Every few minutes we found ourselves pulling over for photos or just to breathe in the scenery. Alaska was no longer surprising us—it was overwhelming us in the best way.

Somewhere along the dusty highway, we stumbled upon a wedding happening right by the roadside. Blue mountains and a shy glacial haze formed the backdrop of their vows. Raj hopped out, congratulated the couple, and even snagged a picture with the bride and groom. Only in Alaska!

Driving on Denali Highway, I realized why Alaska is considered so RV-friendly. There were numerous pullouts on roadside which are perfect for boondocking. Just find a perfect view for yourself and park there. At most places in Alaska, fresh water is free. So, you can fill your freshwater tank easily. You can also find paid sewer dump stations all along the highways or at gas stations at nominal rates of $10. Propane tanks in RV are very efficient. If you are using the propane just for cooking and refrigerator, it can survive for long. See, you really don’t need full hookup sites. Now we realized why most people prefer RV in Alaska as it gave them the flexibility to explore the Alaskan wilderness at their own pace.

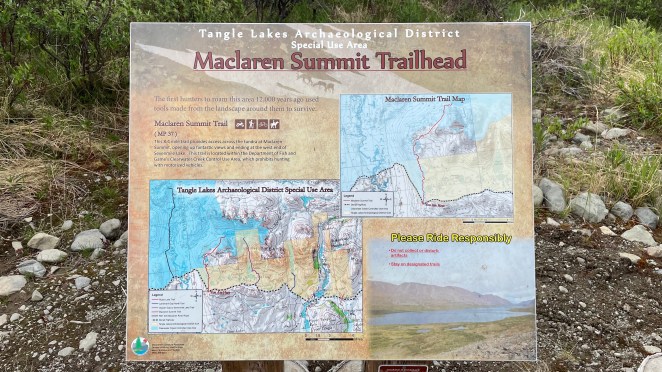

By around 4 PM we reached McLaren Summit Trailhead, the highest point on the Denali Highway. Raj and I braved an off-track hike toward an unnamed glacier, while Shalini and Jyothi rested in RV. Fresh snow lay on the trail, soft and powdery. The glacier peeked from behind thick clouds—vast and silent. On this trail, we could see the tongue of glacier and felt we could really walk up to it. But we were short on time and it was about to rain. The weather and time were not on our side. Even without a clear view, the place felt surreal.

Further east, we reached Tangle Lakes, a serene chain of long, narrow lakes carved by glaciers thousands of years ago. It was 5:30 PM when we stopped here for lunch—hot egg curry and chapati—simple, comforting food that tasted even better against the rugged silence of Alaska. “Ye Haseen Vadiyaan” played on loop from our RV speaker as soft rain brushed the meadows. It felt like a Bollywood scene set in the Alaskan wilderness.

Trans-Alaska Pipeline, and a failed attempt for ice cave

By 6 PM we reached the end of Denali Highway and stood at a fork: turn south toward Glennallen or take an hour-long detour north to visit the Castner Ice Cave. We were in adventure mode, so north it was.

Highway 4 turned out to be spectacular—lupine-lined roads, glacier-topped mountains, and then the first sight of the legendary Trans-Alaska Pipeline System (TAPS). Built in the 1970s after the discovery of oil at Prudhoe Bay, TAPS stretches 800 miles across the state from Prudhoe Bay in north to Valdez in south and crosses one of the most geologically and climatically hostile regions on Earth.

The Earthquake Problem: When the Ground Moves Feet—Not Inches

Alaska sits atop some of the most active fault lines in the world. Entire sections of land can shift sideways by several feet within seconds. If engineers had simply buried the pipeline underground, one major quake would have torn it apart like a straw. To solve this, they elevated more than half the pipeline on vertical steel supports. But elevation alone wasn’t enough. At fault lines—especially the fearsome Denali Fault—the pipeline sits on giant sliding beams that can move side-to-side like a skateboard on a half-pipe. This acts like an accordion. When the ground moves laterally, the zigzag expands or contracts. It has the ability to withstand 20 feet of lateral movement and 5 feet of vertical displacement.

The Permafrost Challenge: A Ground That Melts and Sinks

Permafrost is frozen soil locked in place for thousands of years. But when warm oil flows through a pipeline, that permafrost can melt. And when it melts, the ground can collapse or shift unevenly, creating disastrous instability. To tackle this, engineers lifted the pipeline off the ground in permafrost zones and installed special vertical supports with heat-dissipating fins—giant aluminum “radiators” sticking into the air. These pull heat upward and away from the soil, keeping the permafrost frozen and preventing the earth from sinking. Where burial was necessary, the pipeline was wrapped in thick insulation and sometimes refrigerated using thermosyphons—devices that passively cool the soil even in summer.

The Wildlife Concern: Letting Alaska’s Giants Roam Free

Alaska is not just wilderness—it’s wildlife territory. Massive herds of caribou migrate across the very routes where the pipeline now stands. If engineers had built a solid barrier, it could have permanently disrupted these ancient paths. Instead, the pipeline was raised high enough for animals to pass underneath. In some areas, it arches gracefully across valleys like a steel bridge built just for caribou. Where the pipeline needed to dip underground, the segments were carefully placed so migration wouldn’t be affected.

Seeing this engineering marvel up close, touching the cold steel—felt like standing next to one of the engineering marvels of the modern era. We found a perfect spot to stand right beside the Trans-Alaska Pipeline again. We ran her hands over the steel. It felt like touching a piece of Alaskan history.

Castner glacier ice cave hike

We reached the Castner Glacier Ice Cave trailhead around 8 PM. That’s the magic of Alaskan summers—you can hike under daylight almost 24 hours. A porcupine and standing chipmunk greeted us at the trailhead. We had forgotten our bear spray in the RV, so we kept praying that we do not come across a bear. Although bear didn’t show up, but Alaska’s mosquitoes were out in full force—small but fierce. Insect repellent and bear spray are survival tools here, never forget these two when you are out in wilderness. We didn’t see any ice caves. Later we learnt that the caves form in winter when snow bridges stabilize the ice. In summer, they collapse. The hike was good, but to not see the cave was a disappointment.

But then came the tension of fuel crisis. There were no gas stations on Denali Highway and none on Highway 4 so far. Our RV showed 39 miles of gas left. The nearest station in Glennallen was 32 miles away and the one after it another 3.5 miles ahead. We were cutting very close in terms of fuel. It was already 10:30 PM and worse, we had no idea if it would be open. Raj drove like a man possessed—smooth, steady, conserving every drop. When we reached the first gas station, it was indeed closed. We move forward to the next one. When we finally rolled into the Glennallen’s lone gas station open at that night relief washed over us like warm sunlight. And the fuel tank reading still showed 7 miles remaining (compared to 39-32-3.5=3.5). He drove even more efficiently!

Exhausted but grateful, we reached Ranch House RV Campground close to midnight. We had coordinated with the camp owner. She had left a small note with instructions at the office door.

We parked, settled in, and slipped into a deep, peaceful sleep, the sound of rain tapping softly on the RV roof. Alaska had tested us today, but it had also gifted us some of its most unforgettable moments.